In L.A. Opera’s ‘Otello’, revisionist staging cannot dampen firestorm in the pit and voices

/By Truman C. Wang

5/15/2023

Photo credit: Covery Weaver / L.A. Opera

Visitors to Sant’Agata, Verdi’s home of over fifty years, will find two books by his bed – Carlo Rusconi’s Italian translation of Shakespeare’s complete works, and A.W. Schlegel’s influential Lectures on Dramatic Art and Literature. To his detractors after the 1845 premiere of Macbeth, Verdi described Shakespeare, “whom I have had in my hands since earliest youth, and whom I read and reread constantly.”

Whether Joel Ivany, director of L.A. Opera’s new Otello, has studied Verdi since his earliest youth is another story. While he handles the Otello-Iago scenes with skill and flair, he falls flat in the Otello-Desdemona scenes. There are no three kisses where the music (and Verdi) demands them; the lovers appear emotionally distant from the start, making the abuse and eventual murder seem not all that surprising. There is also unintended comedy that detracts from the drama: Desdemona overreacts each time her plea for Cassio’s pardon gets rejected; in act four, Otello dressed and walks in like the humanoid robot from The Day the Earth Stood Still. Verdi gave very specific instructions in his staging books; directors who take too much liberty do so at their peril.

The fifteen-year-old John Cox production, with its slanted, curved stage flanked by two giant cubes, serves symbolic and psychological purposes – the tossing of Otello’s ship in a fierce storm, the psychological and emotional storms in the rest of the drama. Portable heat lamps replaced campfire in “Fuoco di gioia”; a desk and chairs replaced Desdemona’s bed and pillows (she dies from strangulation by a metal chain, not asphyxiation under a pillow.) The visually unappealing décor is made palatable by Jason Hand’s excellent dramatic lighting in key moments.

Fortunately, L.A. Music Director James Conlon took no such liberty with Verdi’s score (no cuts in act two chorus or act three concertato finale). From the violent crash of the opening storm, to the radiant high strings evoking the starry skies for the lovers (rudely interrupted by ill-timed applause), and emotional gravitas of the concertato ensemble, Conlon treated the score like a Wagnerian symphonic tone poem. (Verdi heard Lohengrin in Bologna in 1871 and Tannhäuser in Vienna in 1875.) It was an energetic, exciting, and intense realization of the drama in orchestral terms. A small cavil should be noted here: At the moment Otello throws Desdemona to the ground (“A terra! E piangi!”), before beginning the concertato, there is a series of orchestral tutti chords, each one marked diminuendo by Verdi; they were all played forte by Conlon.

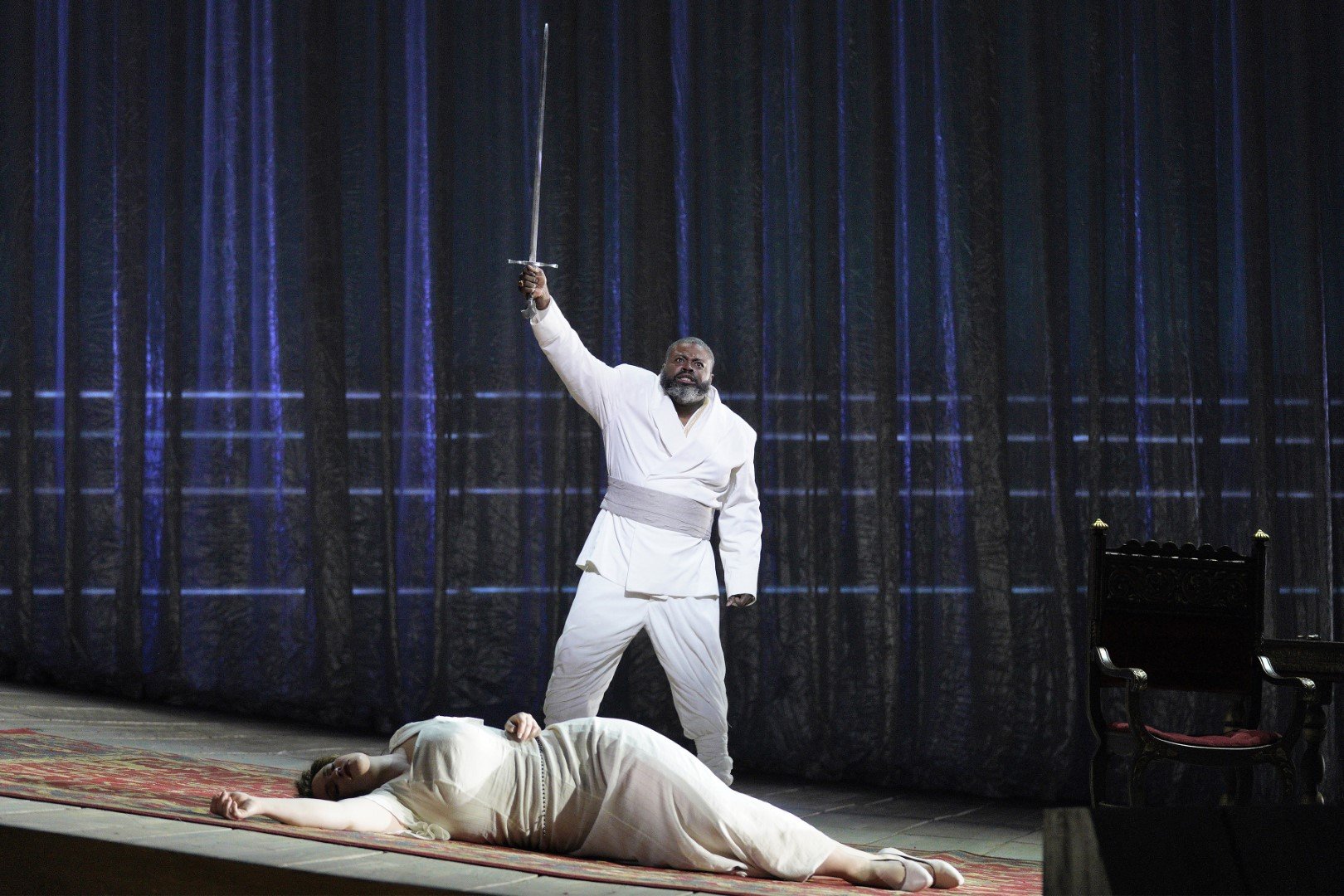

When the last time Otello was seen on the Dorothy Chandler stage, in 2008, English tenor Ian Storey portrayed the moor in blackface (also conducted by Conlon). How time flies and tastes change. Russell Thomas, the Otello in 2023, has grown in stature and vocal command since his Hollywood Bowl performance five years ago. Thomas is an Otello who has the vocal merits and musical intelligence to stand up to the greatest Otellos of the past – Martinelli, Vinay, Domingo, and my favorite, Vickers. The role calls for a tenore di forza, but even as a lyric-spinto tenor, Thomas, singing mezza voce in “Dio! Mi potevi scagliar” (act three), managed to convey the depth of Otello's inner anguish and the sense of a noble soul struck down by jealousy.

Rachel Willis-Sørensen, the Desdemona, was no shrinking violet next to her warrior husband. She showed great pride and anger in their act three scene together. (After all she had the spunk to defy her parents to marry a black man. Incidentally, when visiting Venice, it’s worth checking out Desdemona’s house Palazzo Contarini Fasan, a beautiful Gothic structure opposite of the Church of Salute.) Vocally, she floated beautiful soft high notes in the Willow Song and Ave Maria, and gave a heartbreaking outburst of “Addio!” to Emilia. (It bodes well for her Violetta next season!)

Like Thomas’ Otello, baritone Igor Golovatenko’s essentially lyric voice is also on the lighter side for Iago but he used it well. Unfortunately for him, the role requires more acting, more gravels in the voice than beautiful singing alone to convey Iago’s evil in the “Credo”, or in the sinister cry of “Ecco il Leone!” Iago is no sociopath. He readily admits what he did was evil and that he “believes in a cruel God.” This is in contrast to the evil-doers today who will do everything that Iago did, but plead “not guilty” and hide their villainies behind their attorneys.

The principals were well supported by bass Morris Robinson’s Lodovico (in much better voice than his King Marke I heard in Seattle’s Tristan und Isolde last October), tenor Anthony Ciaramitaro’s Cassio, mezzo-soprano Sarah Saturnino’s Emilia (no shrinking violet either), and tenor Anthony León’s Roderigo

The chorus in Otello, like Iago’s “Credo”, was Verdi and Boito’s addition to the Shakespeare play; they create the space for the protagonists to act in. The L.A. Opera Chorus and the Children’s Chorus filled part of that space with sharp, dynamic singing.

Truman C. Wang is Editor-in-Chief of Classical Voice, whose articles have appeared in the Pasadena Star-News, San Gabriel Valley Tribune, other Southern California publications, as well as the Hawaiian Chinese Daily. He studied Integrative Biology and Music at U.C. Berkeley.