Maria Callas At 100: La Divina or La Traviata?

/By Raymond Beegle

1/23/2024

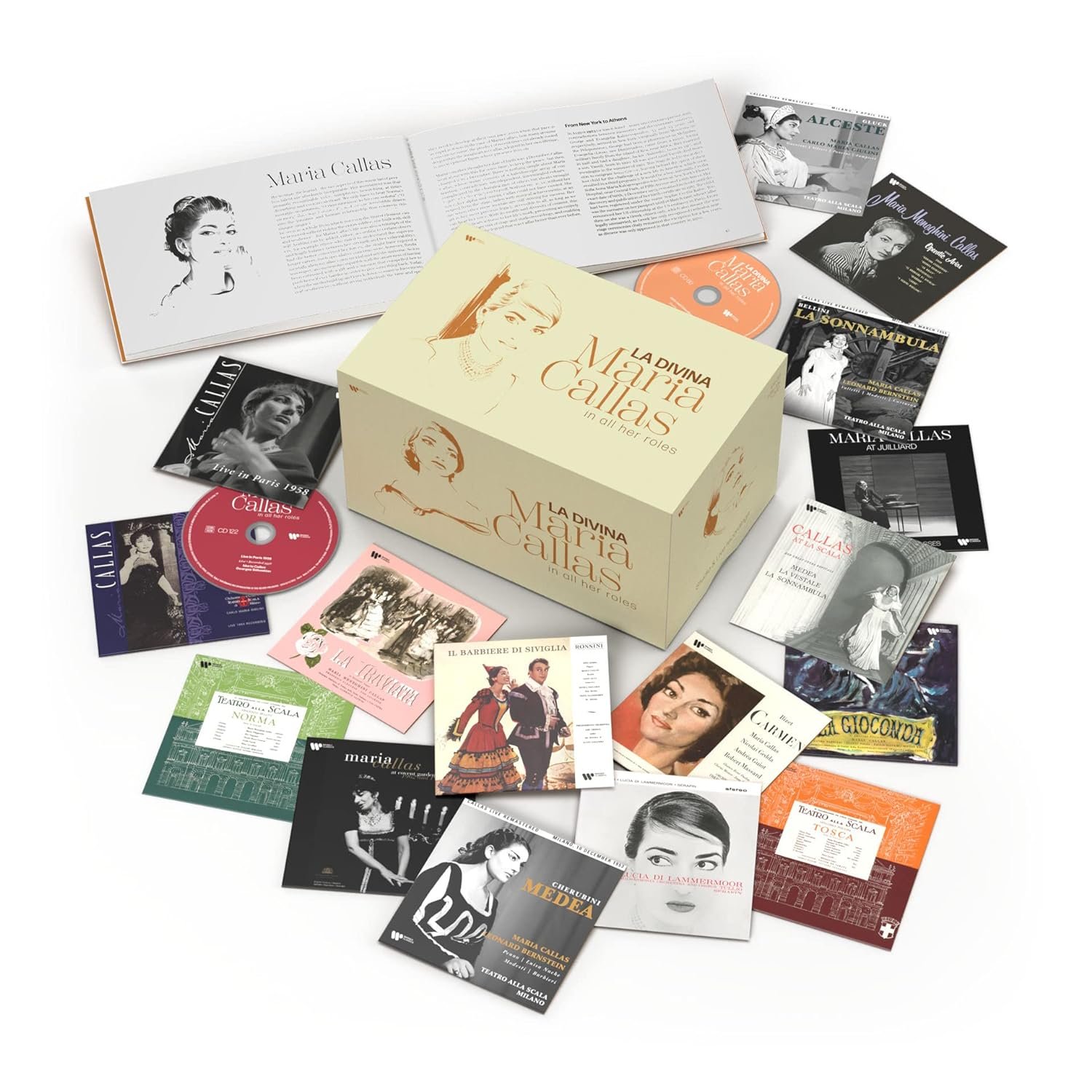

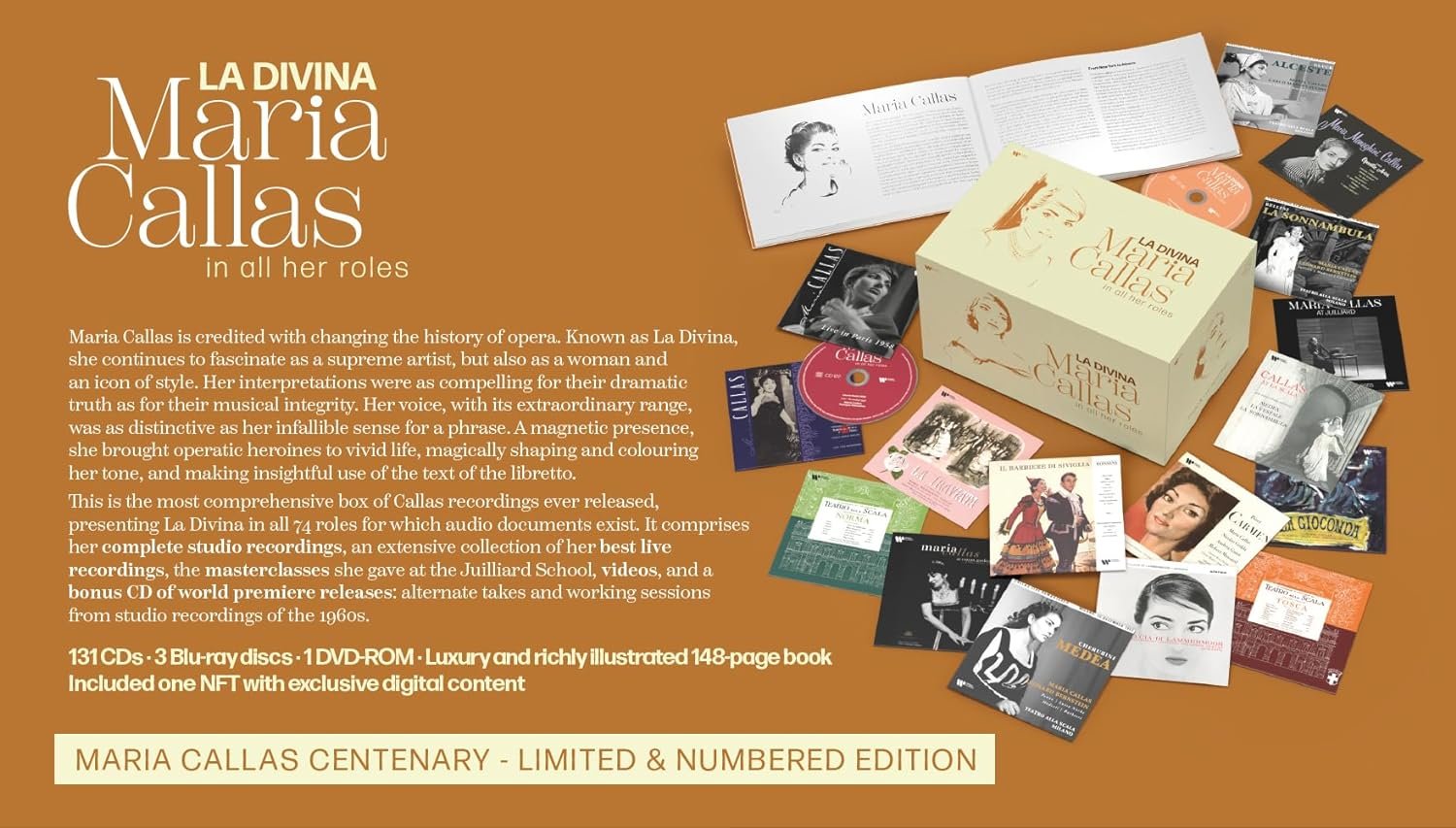

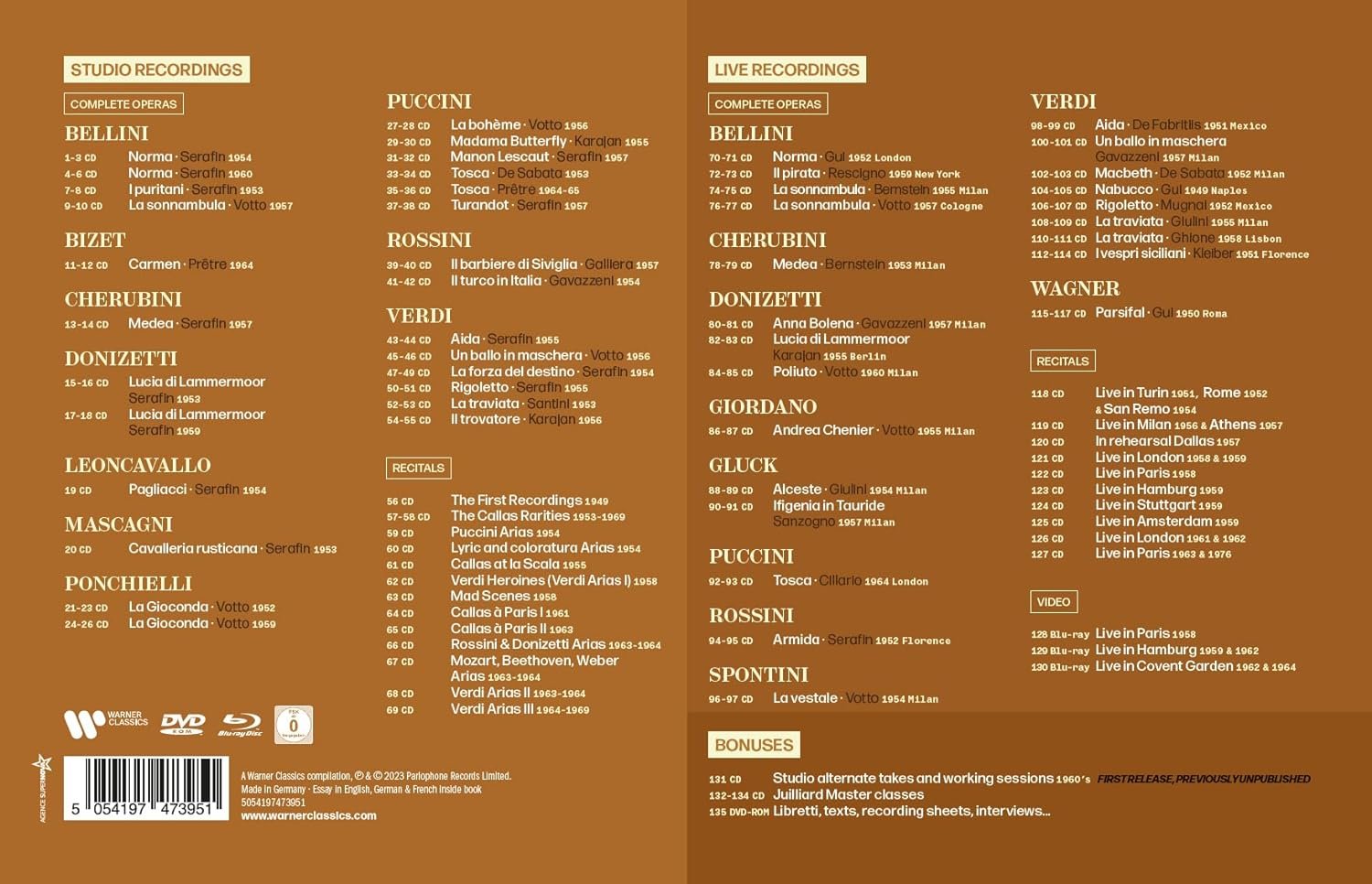

Recordings of every note sung, every word uttered by Maria Kolagorugus, known to us as Maria Callas, are readily available on the internet, and in honor of her centenary, Warner Classics/Erato has also compiled “La Divina,” a luxurious set of 131 CDs, three Blu-Ray DVDs and a DVD video. When listened to chronologically, it proves to be a sad document tracing the steady, ineluctable decline of a musician who achieved heights at an early age, but by 41, despite her dramatic genius, technical knowledge, and innate musicality, found herself with an irreparably damaged voice that could no longer do her bidding.

Notable among the spoken words are the 1971 “masterclasses” at Juilliard, given when the “master” had long been in vocal crisis. It seems to go unnoticed by students and presenters that the singer, who should have been at the zenith of her career, was giving authoritative instructions based on premises that had brought about her vocal ruin.

Interviews cover the entire span of her career revealing charisma and a brilliant intellect. Callas spoke English, French, Italian, German and Greek fluently, and expressed her remarkable ideas with clarity and eloquence, whether it be about art, the beau monde, or the workings of mind and heart. The person - rather, the persona - being interviewed is very much like one of the the 47 heroines she portrayed, but this heroine of the interviews is not as convincing as the Violetta or Lucia she presented to the public. The elegant, reasonable, infallibly right and righteous personality in the Louis XV chair or handsome salon, seems almost a caricature, suspiciously postured and insincere.

Studio recordings reveal that for perhaps five years the young Callas had vocal cords of iron and was the victor of every challenge. The first solo disc, which offered both lyric and dramatic arias (1949) was a stunning success. Her dramatic power, deft sense of style, and vocal control were beyond reproach. The pitch was steady, and the tone spun luminously.

A flood of complete operas was produced, and although roles like Aida (1951) and Tosca (1953) which require more beauty and breadth of voice, the belcanto pieces I Puritani and Lucia di Lammermoor, both in 1953, and Verdi’s La Traviata (1952), are superlative achievements; especially her fioratura in all this material is nothing short of dazzling.

However, when one sings too high and too loud too often - or simply, too often - even iron vocal cords lose their resilience. The pitch begins to waver: An uncontrollable fluctuation between the intended note and the note just below sets in; hollowness of tone appears as beauty disappears; the voice becomes divided into registers (high, low, and middle) without any organic connection between the three; finally, an inability to sing the fioratura passages with accuracy sets in.

Live performances reveal a musician who prefers the sensational to the artistic. An E-flat above high C in the Act II finale of Aida which clashes with the harmonies of the orchestra, or the overblown fortissimos in Weber’s “Ocean, thou mighty monster” are evidence that the singer, striving for a vocal effect, disregards moderation and asks of her voice more than it can deliver. Natural limits of range and dynamics are ignored and the inevitable consequences begin to unfold.

It is an unprecedented phenomenon in operatic history that as Maria Callas began her premature and swift vocal decline, public adulation exponentially increased. She is, perhaps, the first classical performer to become a kind of pop icon, attracting many unschooled listeners who were enchanted by her celebrity, elegant clothes, and beau monde lifestyle more than for her artistry. The noise of glamor and scandal gradually deafened many listeners to the quality of the music she was making, and Callas herself was one of the few that seemed to notice. The closeness of a television camera reveals aspects of personality unseen in a large theater. The grand gesture cannot disguise subtle facial expressions that betray Callas’s discontent with herself, or the radical change in personality seen in a lightning glance or authoritative word given to the conductor, belying the humble sweetness shown the viewers.

One cannot help but feel compassion for the 39-year-old artist in Hamburg (1962), or the 51-year-old in Tokyo, who retains only a ghost of a voice, and whose face expresses despair at not being able to reach the artistic heights she so desperately desired. How must she have felt upon hearing ovations from the crowd, while knowing how utterly she had failed?

Readers might be surprised to learn that Callas was soundly and roundly booed during her first six performances at New York’s Metropolitan Opera House, as well as her final appearances at La Scala, while others began calling her “the voice of the century,” or “La Divina.” Perhaps, no singer has ever been so controversial, but one can find virtually unanimous agreement among fellow artists of the previous generation: Dramatic soprano Gina Cigna said, “She had great presence, but goodness, she sang with three voices!” Soprano Augusta Oltrabella said, “Why, oh why did she not stick to the coloratura repertoire? In that she was truly sensational, but the rest of the voice was simply manufactured.” Lyric soprano Mafalda Favero: “She was theatrical to a degree, but never touching.” Mezzo-soprano Giulietta Simionato: “I always found her interpretations immensely dramatic but never moving.”

The singing of Maria Callas was not divine; it had too many flaws. Her acting was formidable, but opera is about singing, “bel canto,” the beauty of the human voice and what it can express. For an audience to tolerate and even cheer technical failure and breeches of good taste, to disregard the standards of a centuries-old tradition, is a terrible indictment against a public, perhaps a society, who can be persuaded to cheer almost anything. It is also an indictment against the artist, Maria Callas, who ultimately chose glamor and sensation over art, and found that art, in its turn, abandoned her.

Raymond Beegle reviews classical music and opera for the New York Observer and Fanfare Magazine. For many years he was Contributing Editor of Opera Quarterly, the Classic Record Collector (UK), and also appeared on The Today Show (NBC) and Good Morning America (CBS). As an accompanist, he has collaborated with Zinka Milanov and Licia Albanese. Currently Mr. Beegle serves on the faculty of Manhattan School of Music in New York City.