The Hungry Wagnerite

/By Truman C. Wang

Special to Classical Voice

In his 1883 booklet "The Perfect Wagnerite", George Bernard Shaw tries to educate his non-musician readers about Wagner's immense new Gesumtkunstwerk ('total work of art'). Those faithfuls who traveled to the 'Wagner Shrine' in Bayreuth faced another immense task of finding sustenance to get them through the week-long 'Ring' tetralogy. When Richard Wagner built his Festspielhaus in Bayreuth, he probably underestimated the torrents of pilgrims that would inundate and overwhelm the sleepy Bavarian village. One of the visitors to the first Bayreuth Festival in August, 1876 was Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky who, as correspondent for the Russian newspaper ‘Russky Viedomosty’, painted a dire picture of hungry patrons fighting for survival.

In the article dated 8/13/1876, Tchaikovsky wrote, “Yesterday the performance of "Rheingold" took place. From the scenic point of view it interested me greatly, and I was also much impressed by the truly marvelous staging of the work. Musically, it is inconceivable nonsense, in which here and there occur beautiful, and even captivating moments.”

“Towards 10pm, the performance ends and now begins the most bitter struggle for life – that is, a battle for a place in the Theatre restaurant. Those visitors who have no luck there stream back into the town only to experience an even more terrible disappointment. In the inns every seat is taken – one thanks God if one is able to find a piece of cold meat and a bottle of wine or beer. I saw a woman in Bayreuth, the wife of one of Russia’s most influential men, who had no eaten one meal during the whole of her sojourn in Bayreuth. Coffee was her sole succour.”

Tchaikovsky, circa 1876

“I made a little excursion through the streets of the town. They swarmed with people of all nationalities. The reason for this anxious search I discovered only too soon, as I myself had to share it. All these restless people, wandering through the town, were seeking to satisfy the pangs of hunger, which even the fullness of artistic enjoyment could not entirely assuage. The little town offers, it is true, sufficient shelter to the strangers, but it is not able to feed all its guests. So it happened on the very day of my arrival, I learnt the meaning of the words ‘struggle for existence’. There are very few hotels in Bayreuth, and the greater part of the visitors find accommodation in private houses. The tables d’hôtel prepared in the inns are not sufficient to satisfy all the hungry people; one can only obtain a piece of bread, or a glass of beer, with immense difficulty, by dire struggle, or cunning stratagem or iron endurance. Even a modest place at a table, when it has been obtained, is not the end – it is then necessary to wait an eternity before the long desired meal is served. Anarchy reigns at these meals; everyone is calling and shrieking, and the exhausted waiters pay no heed to the rightful claims of an individual. Only by the merest chance does one get a taste of any of the dishes. In the neighborhood of the Theatre is a restaurant which advertises a good dinner at two o’clock. But to get inside it and lay hold of anything in that throng of hungry creatures is a feat worthy of a hero. I have dwelt on this matter at some length with the design of calling the attention of my readers to this prominent feature of the Bayreuth melomania. As a matter of fact, throughout the whole duration of the Festival, food forms the chief interest of the public; the artistic representations take a secondary place. Cutlets, baked potatoes, omelets – all are discussed much more eagerly than Wagner’s music.”

It's important to note that Tchaikovsky undertook the journey mainly to take a cure in Vichy for his old stomach ailments, and managed to fit Paris and Bayreuth into his itinerary. Given what we know about Tchaikovsky, it's not surprising that he aligned his sympathies more with the Bayreuth pilgrims than with Wagner's music drama, which caused him "total mental and physical exhaustion". However, he assured his readers that he shall make a "detailed analysis [of the music] in the distant future" after further studies and repeated listening. Poor Tchaikovsky, he could probably use another cure in Vichy afterward.

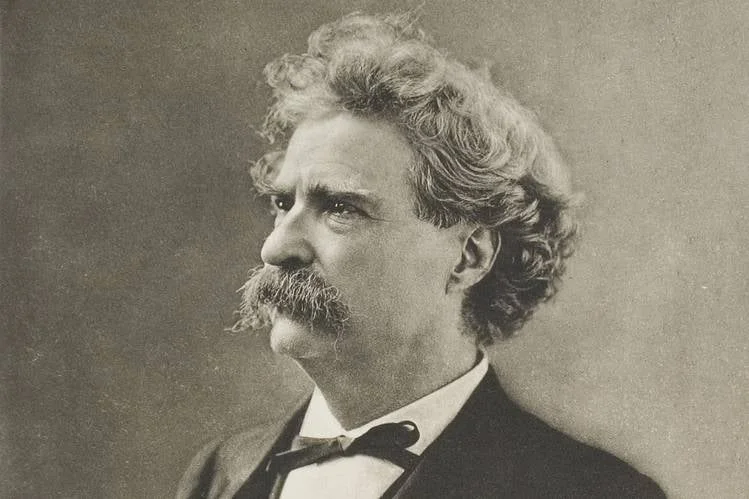

Mark Twain, circa 1890

Exactly fifteen years after Tchaikovsky’s visit, things in Bayreuth had improved little. Mark Twain traveled there to see his favorite Wagner opera “Tannhäuser” on 8/2/1891 and offered the following survival tips –

“To such as are intending to come here in the Wagner season next year I wish to say, bring your dinner-pail with you. If you do, you will never cease to be thankful. If you do not, you will find it a hard fight to save yourself from famishing in Bayreuth. Bayreuth in merely a large village, and has no very large hotels or eating-houses. The principal inns are the Golden Anchor and the Sun. At either of these places you can get an excellent meal – no, I mean you can go there and see other people get it. There is no charge for this. The town is littered with restaurants, but they are small and bad, and they are overdriven with custom. You must secure a table beforehand, and often when you arrive you will find somebody occupying it. We have had this experience. We have had a daily scramble for life; and when I say we, I include shoals of people. I have the impression that the only people who do not have to scramble are the veterans – the disciples who have been here before and know the ropes. I think they arrive about a week before the first opera, and engage all the tables for the season. My tribe have tried all kinds of places – some outside of the town, a mile or two – and have captured only nibblings and odds and ends, never in any instance a complete and satisfying meal. Digestible? No, the reverse. These odds and ends are going to serve as souvenirs of Bayreuth, and in that regard their value is not to be overestimated. Photographs fade, bric-à-brac gets lost, busts of Wagner get broken, but once you absorb a Bayreuth restaurant meal it is in your possession and your property until the time comes to embalm the rest of you."

OK Mark, we get it. You had to fight hard for your food and, once obtained, it did not taste very good. Fast forward to 2016, Bayreuth is still pretty dead outside of the 30 days/year Wagner Festspiele, but has more watering holes and lodging options now. Some hotels even have the Festspiele courtesy shuttle. But that's the subject of another article.