LA Opera’s New ‘Pelleas’: A Well-Sung, Well-Lighted Play

/By Truman C. Wang

3/26/2023

Photo credit: Craig T. Mathew | LA Opera

Claude Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande has not been seen on the Dorothy Chandler stage since 1995, when Esa-Pekka Salonen conducted and Peter Sellars updated the setting to a Malibu beach house. The current production, in period décor by Rae Smith and directed by David McVicar, came from the Scottish Opera in 2017. This is one of the strongest, sharpest, most moving accounts of Pelléas I have ever heard (emphasis on “heard”) – because it was so well sung, so well acted, and so well played.

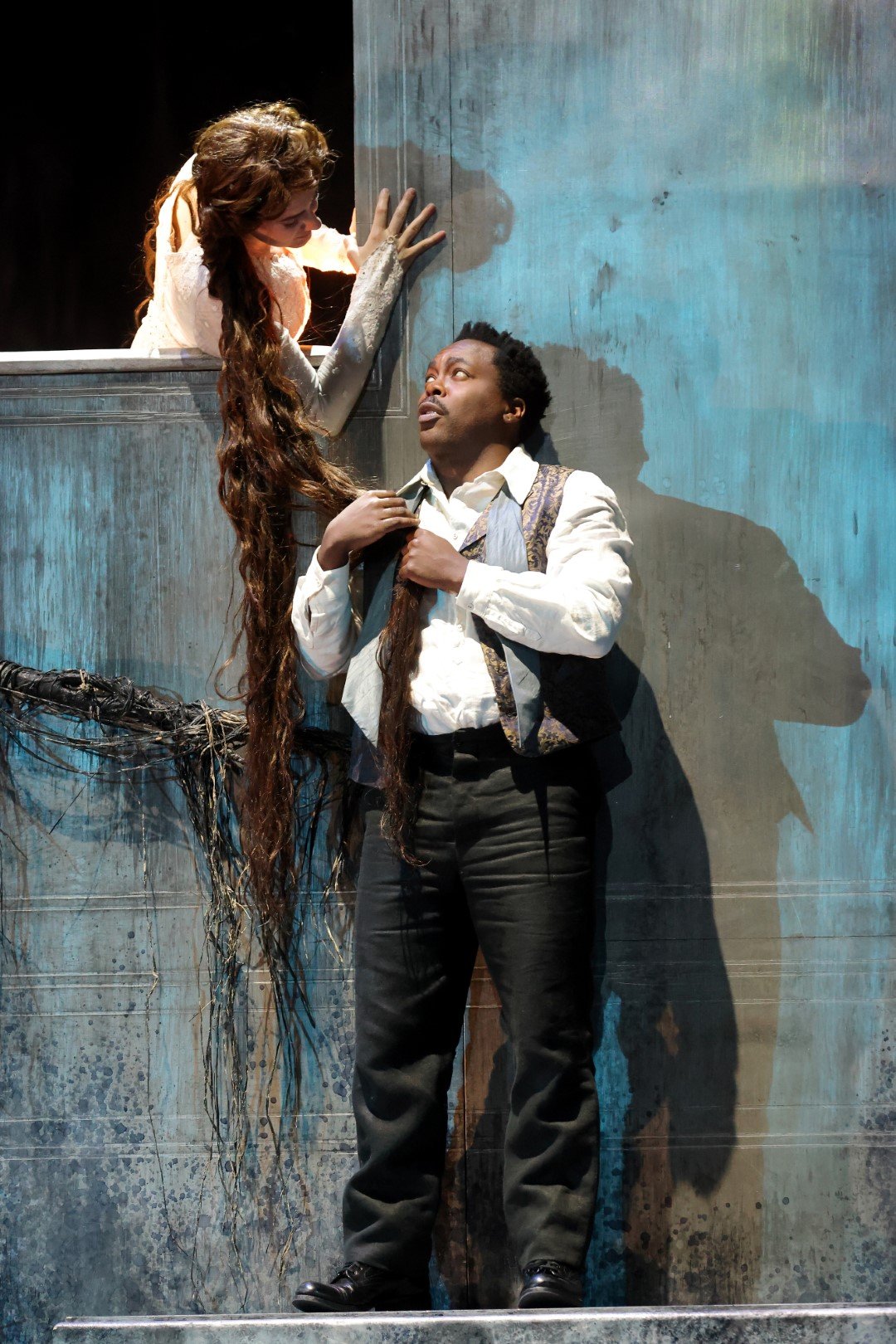

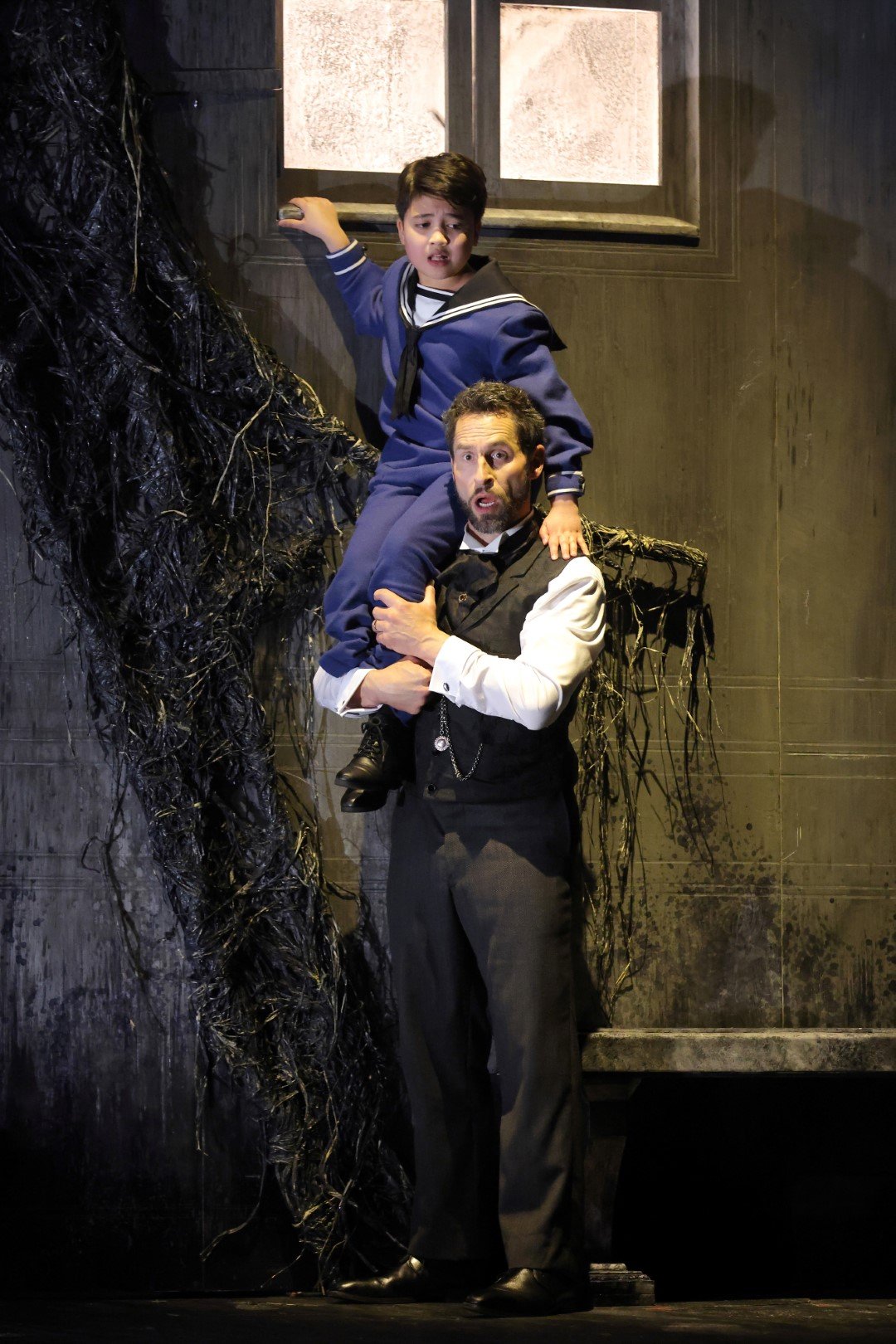

Visually, McVicar’s single set of a castle courtyard with imposing high walls is at odds with the opera’s symbolist imagery. Scene after scene, we see the same set, now with a new partition wall and a door to reveal a room in the castle, now with another wall and a high window for Mélisande to drop down her long tresses. The prosaic set is made tolerable by Pablo Santiago’s often poetic lighting effects that allow us to feel, if not see, “a mist hanging over the sea, sunless forests, sinister grottos, vanishing ships in fog, dark stirring wells.” (The poetic prose of Maeterlinck’s play has more rich imagery than most verse.)

I am, for the most part, in favor of opera sung in the audience’s vernacular. In Pelléas, whose music is closely tied to the rhythms and inflections of the French language, it perhaps has the most to lose. But the gain, in my view, is well worth it, simply due to the fact that the more nearly a musical line is linked to its words, the more imperative it is that the words be used and understood (Hugh MacDonald made a good singing translation for the 1981 ENO production.) In the current LA Opera staging, Mélisande’s important line at the beginning of the Act 4 love scene, “Laissez-moi dans la claret” (“Let me stay here in the light…”) was not translated. The flagrant omission of these words, deep with Wagnerian implications, would have been immediately noticed if they were sung in English.

Despite the translation issue and the uninspiring décor, the director presented a dreamlike drama played by “real people” with naturalness of acting, and the musical standards were very high indeed. Sydney Mancasola was a near-ideal Mélisande: neither the fey, frail wraith of some productions nor the knowing, willful little waif, but a credible, touching young creature. Her singing was true and beautiful. Will Liverman, the Pelléas, had the same directness and naturalness. (Their kiss on the mouth in the love scene’s climactic moment was so shockingly spontaneous it drew gasps from the audience.) Kyle Ketelsen (Golaud), Ferruccio Furlanetto (Arkel) and Susan Graham (Geneviève) were all distinguished. Kai Edgar, the boy treble Yniold, acted well, but for the amount of music he has to sing in Act 4 Scene 3, a woman would have been preferable and more audible. James Conlon’s musical direction was at once lucid and poetic, aiming for Mozartian purity rather than Wagnerian richness.

Pelléas will always be a connoisseur’s opera, even though its final scene is as tragic and bone-chilling as Mimi’s death in La Bohème. There are no heart-on-sleeve arias and duets, no memorable tunes to speak of, only poetic prose set to the most colorful and delicate music in all of opera.

Additional performances of Pelléas et Mélisande are on April 2, 5, 8, 13, 16

Truman C. Wang is Editor-in-Chief of Classical Voice, whose articles have appeared in the Pasadena Star-News, San Gabriel Valley Tribune, other Southern California publications, as well as the Hawaiian Chinese Daily. He studied Integrative Biology and Music at U.C. Berkeley.