A Night with Mozart and Salieri, and the Amazing Pacific Chorale

/By Truman C. Wang

5/21/2022

Photo credit: Doug Gifford

Poor Salieri! The much older, much-maligned colleague of Mozart’s was a dependable, dutiful servant in the royal court of Franz Joseph I. Antonio Salieri’s music, while not bursting at the seams with originality, has loads of charm and high sentiments, as exemplified in his opera Falstaff. The famed Italian mezzo-soprano Cecilia Bartoli even devoted an entire album to Salieri’s music, attempting (unsuccessfully) to salvage his post-Hollywood reputation.

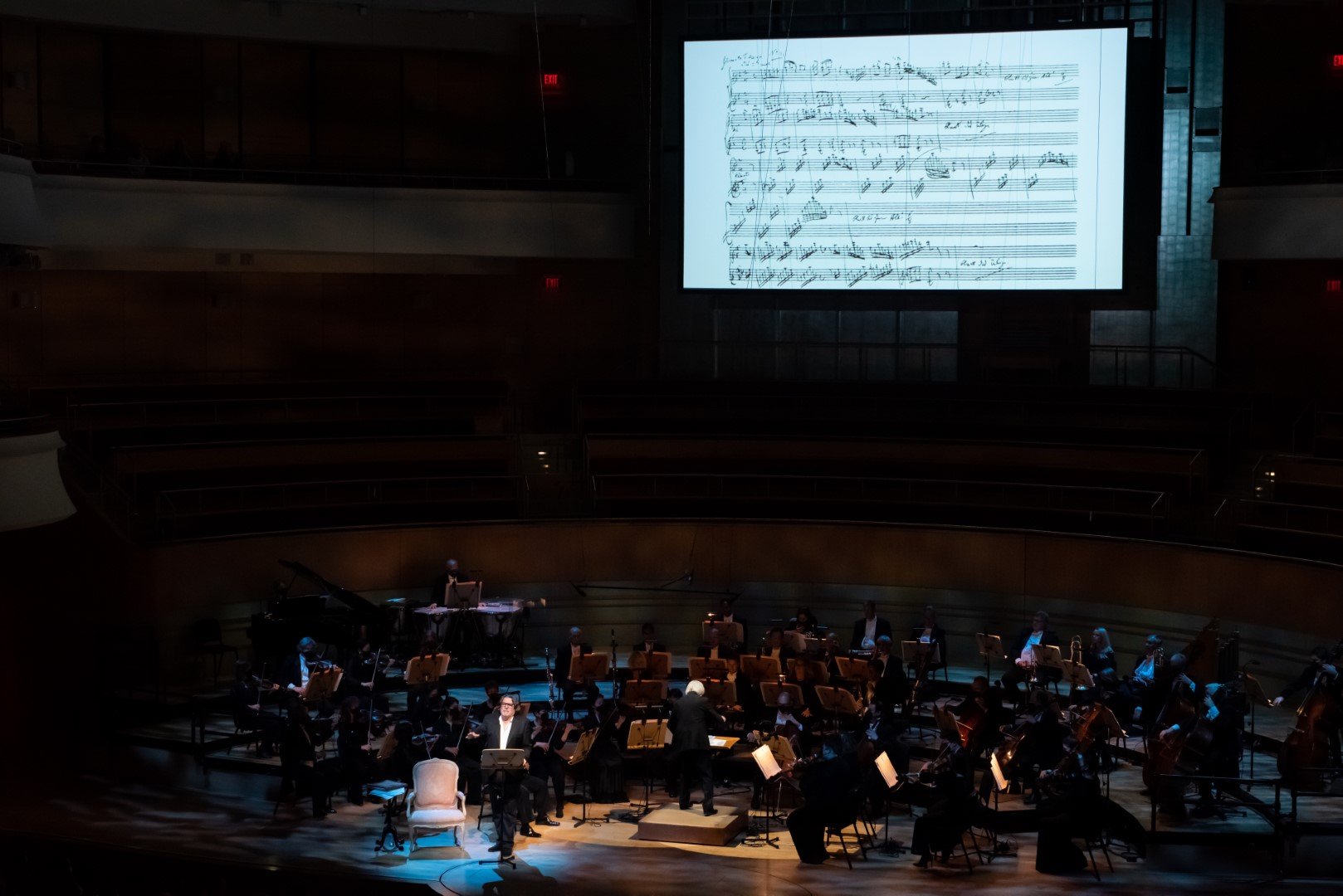

In Saturday evening’s Pacific Symphony dramatized presentation, stage actor Marco Barricelli (from 2016 South Coast Repertory’s production of Amadeus) walked onto the stage as Salieri, to the horrors of the orchestra musicians, and began to narrate his encounters with young genius Mozart. Barricelli could not erase the memory of F. Murray Abraham from the film Amadeus; nonetheless, he managed to inject some semblance of humanity into the Hollywood caricature of Salieri’s character. Sometimes alone, sometimes in background, the orchestra played short excerpts from various Mozart works – Adagio from the ‘Grand Partita’ Serenade, Allegro moderato from Symphony No. 29 in A-Major, “Wie stark ist nicht dein Zauberton” from The Magic Flute, Andante from Sinfonia concertante, K.364 – plus a few bars from Salieri’s Sinfonia in D Major (one yearns to hear more). The Don Giovanni and Marriage of Figaro overtures were given complete, featuring some delightful playing from the Pacific Symphony winds and crackling with fun and drama under Carl St. Clair’s baton.

After intermission, the ‘complete’ Mozart Requiem mass (K.626) was performed. Or rather, Mozart’s Requiem as completed by Robert Levin in 2001. The orchestral playing, under maestro St. Clair, had considerable breadth using the Pacific Chorale forces and a good, though unremarkable, team of soloists (soprano Calena Shafer, mezzo Milena Kitic, tenor John Pickle, baritone Michael Dean).

The Pacific Chorale deserved the highest accolade of the evening, giving thrilling accounts of Dies irae and two reconstructed fugues by Levin (the Osanna fugue and the Amen fugue at the end of Lacrimosa). But they were most memorable in the simple motet Ave verum corpus, in a sublime reading of peace, serenity and otherworldly beauty that, for three minutes at least, delivered the listener from the pains and sufferings of worldly existence.

During his final year, 1791, with a sixth child on the way and bills piling up, Mozart worked feverishly to provide for his family, ironically making more money writing entertainment fluff pieces for rich aristocrats like the German dances, than he did writing serious works like the Ave verum corpus or the requiem. After receiving payment for a piece he wrote for a mechanical organ, Mozart reportedly quipped, “They paid me too much for what I did, but not enough for what I can do.” What he could have done, we shall never know, for he died six months later at age 35.

Truman C. Wang is Editor-in-Chief of Classical Voice, whose articles have appeared in the Pasadena Star-News, San Gabriel Valley Tribune, other Southern California publications, as well as the Hawaiian Chinese Daily. He studied Integrative Biology and Music at U.C. Berkeley.